The reality is alarming—as global HIV-related deaths have declined among children and adults, adolescent deaths have increased. Approximately 1.8 million adolescents (between the ages of 10 and 19) are living with HIV/AIDS, 80% (1.4 million) of them live in Sub-Saharan Africa. This is a 28% increase since 2005. The stark reality is that adolescent HIV rates are projected to continue increasing because of population growth and stalled efforts to combat the spread of the disease.

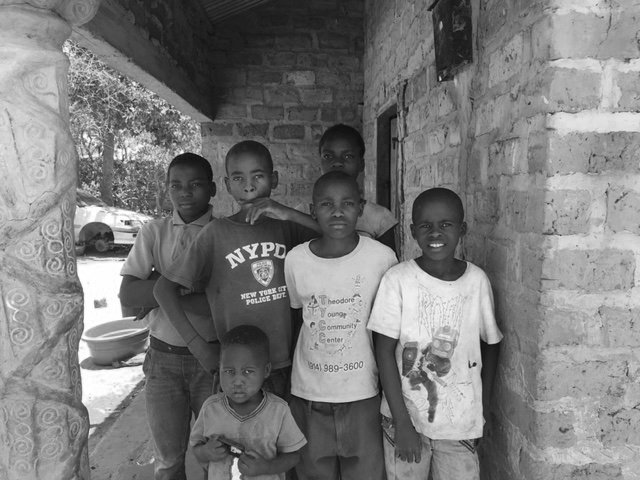

In Zambia, adolescents face unique challenges when it comes to HIV/AIDS. Many young people are not accessing the services they need because youth-friendly HIV services are not widely available. Testing is also not widely practiced by adolescents; fewer than 30% of them have been tested for HIV. Additional barriers are related to their access to education and health services. For example, adolescent HIV/AIDS services are combined with adult ones. Adolescents are often too shy to show up at health clinics on days when adults are also on site to receive services. For those who do show up at the health clinics, they end up missing a school day. As a result, the number of adolescents receiving treatment has decreased. There is also a lack of youth counselors and spaces in health facilities.

Additional barriers to accessing HIV services and other services include relational and individual factors. Relational factors, such as the attitude of family and peers, serves as a determining factor in getting tested for HIV. Adolescents with high levels of social support from friends, including the ability to discuss whether or not to get tested, were more likely to obtain HIV services. The same is true of adolescents who discussed services with family and their sexual partners.

Even when adolescents are receiving antiretroviral treatment, they face barriers for treatment retention and adherence. One of the most significant barrier is fear of disclosure. Both adolescents and their families believe that one’s HIV status should be kept and treated within the home. This corresponds with reports of adolescents taking and keeping their medication in their homes to avoid being exposed as HIV positive. Social events in school and extracurricular activities tend to interfere with dosing time and results in missed medications. Adolescents also delay taking their medication for hours until they returned home or even missing their dose for the day because they slept over at a friend’s house and did not bring it because of their fear of exposure.

(Photo: UNICEF/SUDA2014-XX166/Noorani)

Zambia has undertaken initiatives to address this gap in services, stigma, and other barriers. To reduce the fear of discrimination for having or being suspected of having HIV, Zambia has started a program that provides free, confidential information to adolescents about HIV. Locate services and nearby clinics were also established. Additionally, a mentorship and support program led by other HIV-positive peers was also implemented. While there is still much work that needs to be done, Zambia has taken good steps to provide youth-friendly HIV services.